Pia Fries / Birgit Jensen

20. April – 22. Juni 1997

Jens Peter Koerver

Terrain vague

The idea of the illusionistic image goes back a long way in European art. Anecdotes about deceptive images of people and animals have been handed down from antiquity to the present day. The confusion of reality and appearance, the credible representation of the absent and the real on the picture plane was long considered the supreme triumph of the medium and was at the same time interwoven with a constant reflection on reality, knowledge and the status of the image. Even modernism, in its radical endeavor to drive out all illusion as something false and mendacious from the image, from reality in general, vehemently rejected this tradition. Only the medial upheavals of the last two decades have led to a changed, more differentiated approach. Illusion is accepted as a partial aspect of contemporary reality, permanently permeated by images of all kinds, and staging, construction, and virtuality are no longer apodictically rejected as an amoral deception in favor of a supposedly immediate „true“ world.

In common usage, illusion means „illusion of,“ referring to something seemingly present before one’s eyes, something that otherwise is, was, could be, or should be in the world and is now repeated in a manner specific to the image as an optical illusion. Even if the viewer is aware that, as Maurice Denis wrote in 1890, the painted image is a smooth surface covered with paint in a specific arrangement (or points of light or a stalled chemical reaction) (1), this aspect of material factuality is repeatedly overlooked in favor of the spaces depicted in the image, the suggestion of something else beyond the surface; the reality in the image becomes, for the moment, through the moment, the most immediate reality. Thus, the eye readily succumbs to the peculiarly hybrid reality of Birgit Jensen’s moiré images.

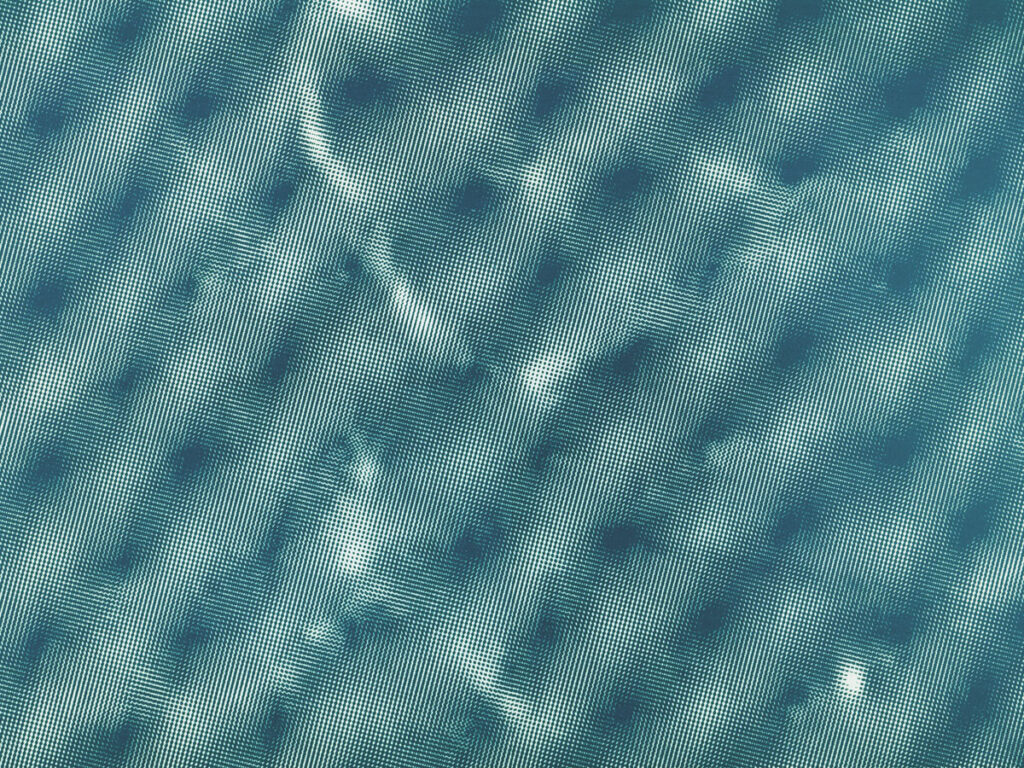

The term moiré has various meanings. For example, „[Moiré] refers to a shiny, cross-ribbed fabric with a typical wavy grain. This occurs when two fabric panels are passed through a calender under pressure. The ribs are partially flattened, resulting in irregular lighting effects.“ (2) In the printing industry, it refers to an error in the reproduction of images. Moiré is originally a negative phenomenon in multi-color halftone printing. It arises from the inaccurate overprinting of individual color halftones, i.e., from the inaccurate superimposition of similar structures. (3) Regardless of the motif, the image surface takes on an uncontrolled life of its own; floating condensations, diffuse waves, and amorphous structures spread like a veil over the image.

For the paintings in the Moiré series, Birgit Jensen intentionally exploits the artistic potential of this error in the mechanical creation of a repetition that strives for the greatest possible similarity to her original. The artist describes her technical procedure as the precise superimposition of slightly different screen frequencies at differing angles, resulting in a specific, deliberate moiré. By provoking and isolating this type of „error,“ the defect of the mechanical illusion creates a different, somewhat autonomous optical illusion in painting.

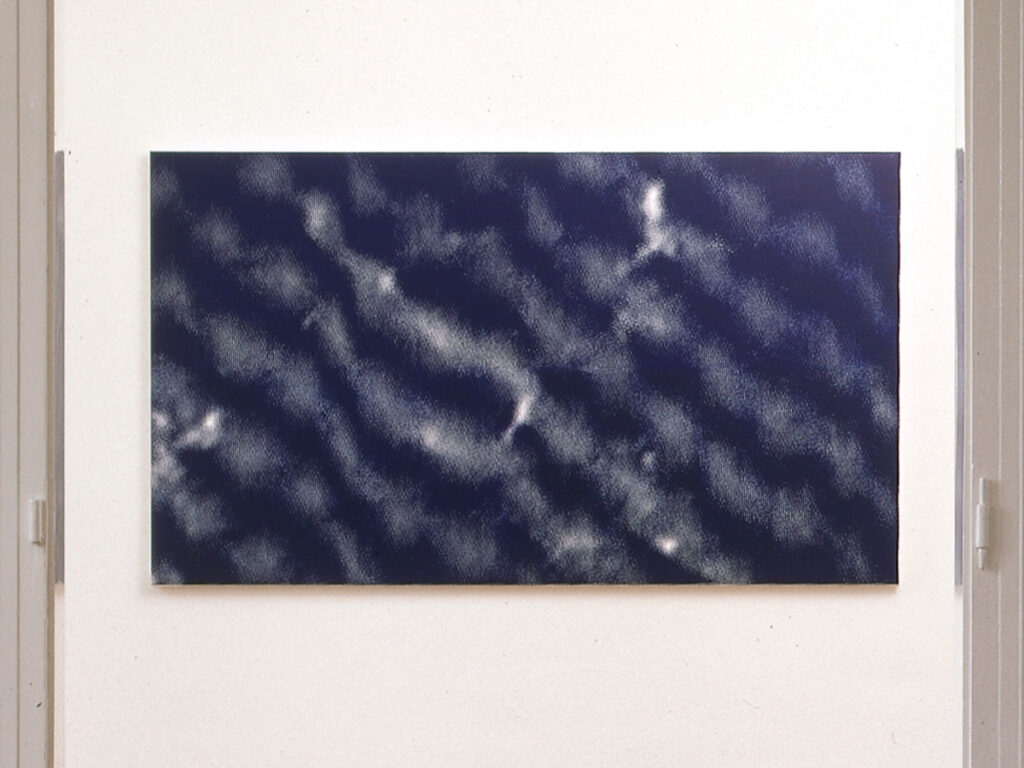

Birgit Jensen’s paintings are paintings. This observation may initially seem surprising, given that the works are produced using the screen printing technique, which explains the uniform, seemingly anonymous application of paint. Painterly decisions here do not concern the manner in which the paint is applied to the canvas. Painterly action takes place at other points in the work process. The means used here are no longer brushes and paints; rather, the extremely fine modulations arise from the diverse reworking of photographic source material on the computer. The aim of the entire work is genuinely painterly, aiming to explore the spatial potential of color through finely nuanced chromaticity and differentiated shifts of light and dark. The works in the Moiré series make particular use of the possibilities of creating three-dimensional illusion through color. Seen from a distance, they convey the impression of a very softly flowing relief, suggesting gentle protrusions into space, elevations and depressions that, despite their absolutely spatial character, exhibit no nameable materiality. Painterly, the color models an appearance that presents itself to the tactile eye and yet remains completely indeterminate. These tantalizingly tangible, physical-spatial appearances and some embedded gradients of light certainly have photographic, i.e., representational, features, and yet nothing other than the described unreal relief is revealed; Spaces that don’t exist, that didn’t exist before the images, a completely invented, media-constructed reality. Like a trace, they preserve a presumptuous, enigmatic objectivity without, however, revealing it.

From a distance, they promise a tactility of the soft and airy, announcing sensations for the sense of touch. But from the proximity to the picture, which allows a tangible examination of what is promised, this promise is lost and transforms into a becoming visible, a revealing of the painting. The representational illusory image dissolves. The close-up view reveals a multitude of differently sized, precise grid dots – one should actually speak of microforms, each of them exhibiting an individual appearance due to processing and material-related irregularities. Partly visible individually, partly joined together by superimposition, individual dots and more or less densely closed dot zones stand sharply contoured and flat on the picture ground. Without withholding anything, the picture reveals all its components. A paradoxical opposition determines the relationship between part and whole, close-up and distant view: hard and soft, clear and diffuse, three-dimensional and flat, sober disclosure of all components and mysteriously >hidden< objectivity.

Detail and the image as a whole are not continuously connected. The image can be seen only in its particularity. The knowledge of the image acquired through seeing does not lead to recognition. The floating and flickering effects of moiré cause vision to constantly drift between tangible parts and the image, which is never visible as a whole. Thus, the image reveals itself in the visual experience as a place of insurmountable difference between visible, yet fragmentary partial aspects and an eluding, solely known totality.

The placeless, floating, vague quality characterizes moiré and also outlines the viewer’s situation. The mediating connection between knowledge and seeing, fundamental to all everyday seeing, is suspended. It is precisely this subversion of cognitive vision that leads to a self-recognition of vision, or at least to the insight into its conditionality: „The observer […] sees more appropriately because he also perceives the place, time, and condition of his own standpoint […]. He observes something, and in doing so, he observes himself. In a previously unknown way, he becomes the originator and designer of his gaze.“(4)

While the pictorial structures used by Birgit Jensen in recent years can be derived from fabrics, architectural details, cityscapes, or even found tables and diagrams, the works in the Moiré series, created since 1996, cannot be directly traced back to reality.

Although they refer to fragmentary depictions of reality (landscapes, fabrics, organic microstructures?) and are highly illusory, no clearly identifiable object is revealed. The images in the Moiré series also differ from possible medial origins. Aspects of photography, rasterized print reproduction, digital screen image, and painting are suspended in them; they playfully embrace the possibility of depiction and simultaneously resist all attempts at attribution. As supposedly medial images, they remain objectless and mysteriously unreal. The acute indeterminacy of these images reveals a doubt about the possibility of making reality tangible and manageable, even and especially with the means of technical and medial access. In the depiction, in the unifying worldview, the flow of reality is elusive. And yet, the perception of this mercurial, branched stream remains dependent on images; alongside language, they are an essential instrument for appropriating reality. including all (dis)appointments.

(1) In Denis’s essay Définition du Néo-Traditionisme, published in 1890, it literally states: „Be rappeler qu’un tableau est […] essentially a plane surface covered with colors in a certain assembled order.“ Quoted here: Maurice Denis: Théories 1890 – 1910. Du Symbolisme et de Gauguin vers un novel ordre classique; Paris 1913, p. 1.

(2) Communication from Prof. Anita Oettershagen, FH Niederrhein, to Birgit Jensen.

(3) See Jörg Michael Matthaei: Fundamental Questions of Graphic Design; Munich 1975, p. 119.

(4) Gottfried Boehm: A Copernican Revolution of the Perspective, in: Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany (ed.): Sehsucht. On the change of visual perception; Göttingen 1995 (Forum series, vol. 4), p. 28.